Astronomy has come an incredibly long way since the founding of the Royal Observatory Greenwich almost 350 years ago, when the first Astronomer Royal John Flamsteed manually mapped the stars with rudimentary telescopes in a quest to measure longitude.

In the last 50 years alone, boundaries have constantly been pushed. Among hundreds of human achievements, there are now a number of probes exploring remote reaches of the Solar System, a hugely complex space telescope 1 million miles away beams images back to Earth, and a lunar space station is being built to help send humans to Mars.

In his new book Diamonds Everywhere, astronomer and former Royal Observatory Greenwich Public Astronomy Officer Tom Kerss explores 101 of the most incredible astronomy discoveries in history – from mind-blowing figures and astonishing sights to strange-but-true discoveries.

Below are 15 of these discoveries that might just change how you see the Universe.

1. Your hair collects space dust from comets

Every day, several tonnes of material falls to Earth from space. Some of it is witnessed on arrival, as a bright meteor may result in a meteorite – a fragment of rock and metal crashing into the ground.

But a great deal of this cosmic material doesn’t make such a spectacular entrance to our planet. Rather, it falls gently through the atmosphere in the form of space dust that is all but invisible to our eyes.

A surprisingly large quantity of space dust lands on our planet: about 5,200 tonnes per year, 100 tonnes per week, or 14 tonnes per day. This dust is made up of tiny particles of rock and metal that have been chipped off asteroids and comets, either in large collisions or by micrometeoroids. About 80 per cent of all this dust originates from Jupiter-family comets, which have orbital periods of less than 20 years.

The particles are so small – at most a few tenths of a millimetre across – that they are not generally visible to the naked eye and can only be detected using specialised instruments. Every time you’re outside, you stand a chance of catching some of this space dust in your hair. It’s very likely you’ve already caught some and later washed it out without knowing it.

Image: Comet C/2016 R2 Panstarrs the blue carbon monoxide comet - rotating comet tails on Jan 19 2018 by Gerald Rhemann, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

2. Some stars are so cool, you could touch them without scalding your hand

In understanding that the Sun is a star, we’ve come to think of all stars as blazing hot, fiery balls of plasma that could melt any material or alloy we could create. But this isn’t true of all stars, and, in fact, there is a category of fascinating, supercool stars lurking within the Galaxy.

Brown dwarfs are colder than any known star and are classified as sub-stellar objects. They are often referred to as ‘failed stars’ because they are too small to sustain nuclear fusion in their cores, which is the process that powers the Sun. As a result, brown dwarfs emit very little light and heat, making them quite challenging to detect.

The surface temperatures of brown dwarfs vary, but one particular subclass – Y-type stars – are the coldest of all. Their surface temperatures are typically only a few hundred degrees Celsius above absolute zero. That corresponds to a temperature of some tens of degrees Celsius. Your skin has a temperature of around 35 °C and a warm mug of tea is just a bit hotter. Were it possible to touch the surfaces of these Y-type stars, you would be able to feel the warmth without even scalding your hand!

Image: Star Icefall by Masahiro Miyasaka, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Copyright of the artist

3. There could be as many as 10 billion Earth-like planets in the Milky Way

In 2019, astronomers combined data from the Kepler Space Telescope with new results from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission, concluding that, on average, as many as one in six stars hosts an Earth-sized planet in its habitable zone. Potentially tens of billions of such worlds are strewn across the Milky Way.

While the search for Earth-like planets continues, the range of environments that can be considered habitable is widening. An exact Earth analogue may not be necessary for complex life and the number of life-supporting havens may be higher than we think.

Image: Moon Balloon © Patrick Cullis. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

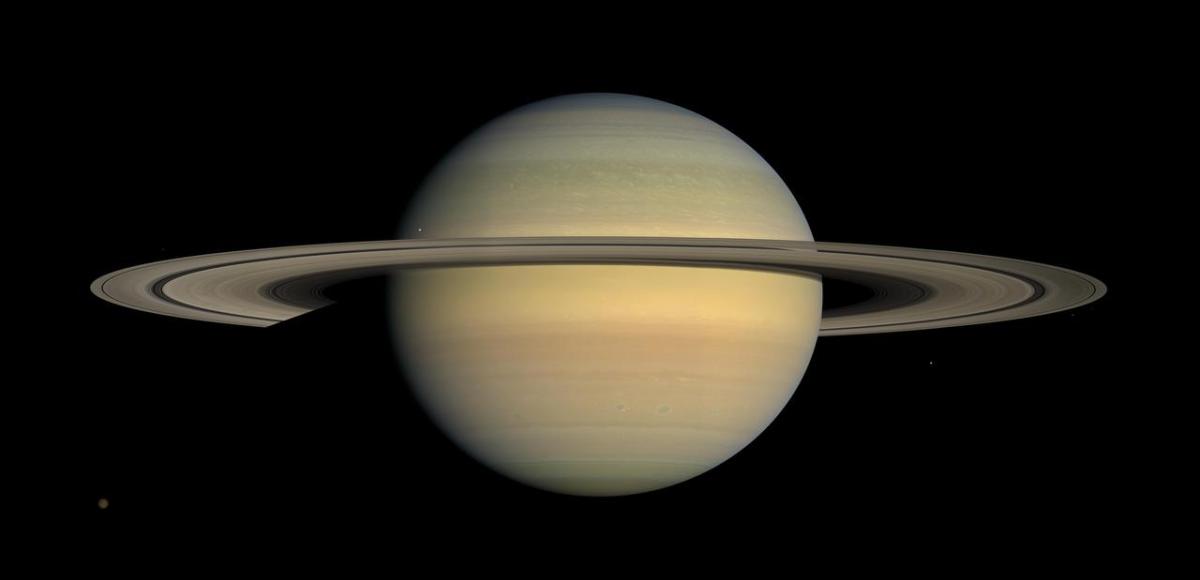

4. Saturn's rings are incredibly thin

Saturn, the sixth planet from the Sun, is known for its spectacular rings that encircle the gas giant. While they appear to be solid and continuous from afar, the reality is that they are made up of trillions of individual pieces of ice and small amounts of rock, ranging in size from tiny dust-like particles to giant boulders.

One of the most remarkable things about Saturn’s rings is their incredible thinness. Despite stretching out to a distance of nearly 140,000 km from Saturn’s equator, the rings are only a few hundred metres thick at most. Put another way, the rings are hundreds of thousands of times wider than they are tall.

For comparison, a Blu-ray disc is 120 mm wide and 1.2 mm thick. To match the scale of Saturn’s rings at this thickness, the Blu-ray disc would need to be about 1 km wide!

Image of Saturn by NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Explore the Universe at the Royal Observatory

5. Precious metals like silver and gold are forged when dead stars collide

The remnants of exploding stars – neutron stars – will sometimes collide, producing and releasing vast quantities of precious metals among many other elements. The energy involved in these collisions is far greater than that released by a supernova. As a result, the heaviest naturally occurring elements, including uranium, are produced almost exclusively by these extreme events.

Both supernovae and neutron star collisions fuse heavy elements through ‘r-process’ nucleosynthesis. They create sufficient temperatures and pressures for atomic nuclei to undergo a rapid neutron capture. These nuclei are forced to absorb neutrons, bulking up their atomic numbers. Merging neutron stars can reach numbers like 47 (silver), 78 (platinum), 79 (gold) and 92 (palladium), making them forges for precious metals. If you invest in these metals, think about where they came from. Perhaps they’ll seem more valuable in light of their extreme origins!

Image: Supernova remnant DEM L 190, credits: ESA Hubble and NASA, S. Kulkarni, Y. Chu

6. The number of stars in the Milky Way is probably higher than the number of humans that have ever been born

Ask an astronomer how many stars there are in the Milky Way and the answer will range from ‘hundreds of billions’ to an approximate value: ‘about 100 billion’; ‘300 billion’; ‘500 billion’. There must be a correct answer, so why does the value vary so much?

Unfortunately, figuring out the number of stars in our Galaxy isn’t just a matter of counting. Most of the Milky Way is obscured from view and the regions we do see are so vast and distant that individual stars aren’t readily identified, even with powerful telescopes. Determining the population of the Galaxy relies upon observations, assumptions and informed estimates.

Curiously, anthropologists are more confident about the total number of human beings that have ever lived – about 110 billion. So, we can say that there are probably more stars in the Galaxy than every human that has ever been born!

Image: Omega Centauri © Ignacio Diaz Bobillo. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

7. Asteroids can have rings and moons

Chariklo is a small celestial body that orbits the Sun between Saturn and Uranus. Chariklo is now known to be a Centaur asteroid – a class of asteroids that are characterised by their unstable orbits, which cross the orbits of the giant planets. What makes this 250 km-wide asteroid so special is that it has a pair of rings around it, making it the smallest known object in the Solar System with a ring system.

Asteroids can also have their own moons. Ida and Dactyl are a pair of space rocks that captured the world’s attention thanks to a striking discovery by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft. During a flyby of asteroid Ida in 1993, Galileo’s cameras spotted Dactyl, a much smaller ‘moon’ that orbits Ida. This pair provided the first observational evidence that asteroids can have their own natural satellites.

Image of Ida and Dactyl by NASA/JPL

8. Shooting stars blaze a range of colours based on the elements they’re made of

Meteors appear when the Earth slams into unsuspecting flecks of ice and rock drifting around the Sun. They immediately find themselves moving through the atmosphere at hypersonic speeds and the air in front of them can’t get out of the way quickly enough. This generates ram pressure, which superheats the air. The air in turn transfers heat to the meteoroid, causing it to vaporise in a flash.

Look carefully when you spot a bright meteor and you may notice some vibrant colour. You can even, on occasion, spot several different colours as the meteor progresses. The brightest, most dazzling meteors, known as fireballs, are more likely to show you these colours as they burn for longer. The colours are associated with different elements, forming compounds trapped in the ice or rock. The compounds are raised to well beyond their burning temperatures and the elements give off varying colours of light. Magnesium shines blue-white or cyan; calcium looks violet; sodium is orange; iron glows yellow-white; nitrogen and oxygen produce distinct reds.

Image: Geminids over the LAMOST Telescope by Yu Jun, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Courtesy of the artist.

Never miss a shooting star

Sign up to our space newsletter for exclusive astronomy highlights, night sky guides and out-of-this-world events.

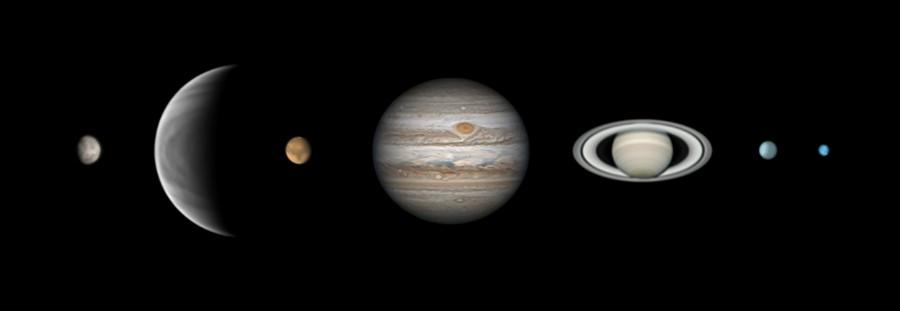

9. Uranus and Neptune may have switched places

The outermost planets, Uranus and Neptune, are often referred to as the ice giants because they are primarily composed of water, ammonia and methane ice. Some simulations suggest that early in their history they effectively changed places, meaning Uranus might once have been the last planet in the Solar System, but it gave the role to Neptune.

An advanced model of the young Solar System’s dynamics, called the Nice model, has been developed and refined since its inception in 2005. In the Nice model, the giant planets formed closer to the Sun and then migrated outwards to their present orbits as the protoplanetary disk dissipated.

Curiously, a significant number of simulations show Uranus and Neptune switching places as they both migrate away from the Sun. It’s possible that Uranus was originally the outermost planet. While this hypothesis is speculative, it could explain one puzzling mystery surrounding Uranus – that the entire planetary system is tilted on its side.

Image: Parade of the Planets by Martin Lewis © Martin Lewis. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

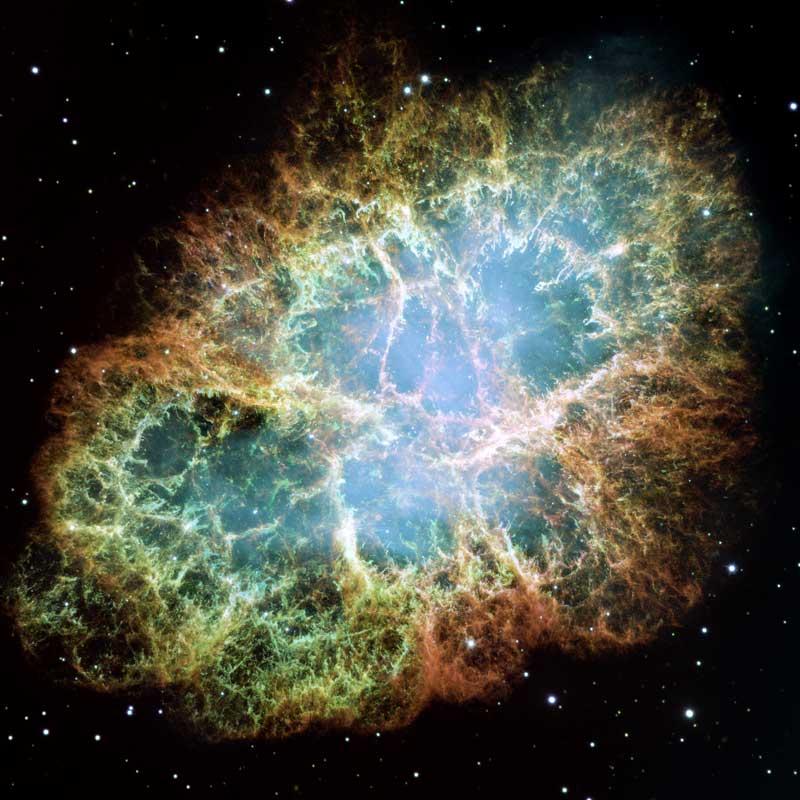

10. You can see what a supernova looks like nearly one thousand years later

In 1054 CE, Chinese astronomers recorded a ‘guest star’ in the sky that was visible for several weeks. Nearly a thousand years later, in the same spot, we find the Crab Nebula. This is a supernova remnant, blasted out into space by the cataclysmic death of a massive star.

As one of the most spectacular supernova remnants in the Galaxy, it’s a fascinating snapshot of an explosion – as chaotic and complex as the event that created it.

Image: Crab Nebula by NASA, ESA, J. Hester and A. Loll

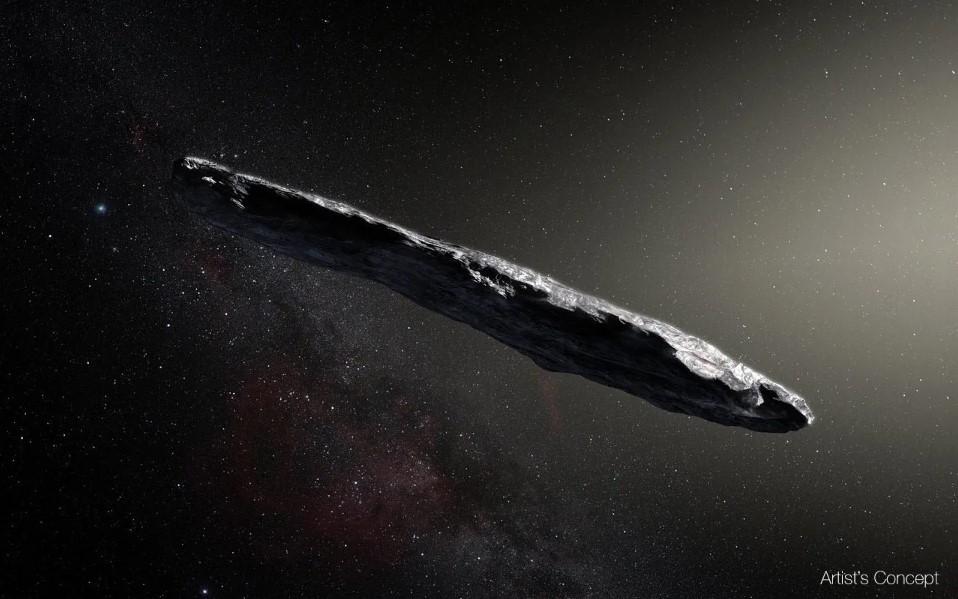

11. A cigar-shaped object named ‘Oumuamua, was the first known interstellar object (from outside our Solar System)

In 2017, astronomer Robert Weryk, working in Hawai‘i, detected a strange object travelling through our Solar System. It was given the name ‘Oumuamua, from the Hawaiian for ‘scout’, after observations confirmed that it was of extrasolar origin. This bizarre, cigar-shaped object was unlike anything that had been seen before and its temporary visit to the Solar System sparked a fierce debate about its origins that continues to this day.

Since ‘Oumuamua was only passing through our Solar System briefly, scientists had to act quickly to gather as much data as possible. They employed a variety of telescopes and other instruments to study the object’s size, shape, composition and trajectory, but only limited information could be gathered before ‘Oumuamua reached an unfavourable distance for observation. As such, little is known about it, leaving the door open for speculation. In 2019, 2I/Borisov – the second known interstellar object – was discovered. It is a rogue comet initially spotted by an amateur astronomer. Astronomers now think such interstellar objects pass through our Solar System on a regular basis.

Image: Artist's concept of 'Oumuamua by European Southern Observatory/M. Kornmesser

12. The Moon is more colourful than meets the eye

Invisible to our eye, the Moon exhibits subtle shades of colour across its surface, which can be teased out by processing photographs, and using sophisticated cameras and software, so we can see a picture of the Moon awash with striking hues. Of course, the colours are unnaturally enhanced to be obvious to us, but they are no less real than the other details we naturally perceive.

Astronomers have for centuries described very faint hints of colours visible on the lunar surface through telescopes. Mare Tranquillitatis (the Sea of Tranquility) was known for its blueish tint. Palus Somni (the Marsh of Sleep) has a reputation for being slightly sandy in colour. Of all the colourful regions to hunt down, the Aristarchus Plateau is widely considered the most conspicuous. This enormous block of highland terrain rises above the volcanic plains of Oceanus Procellarum (the Ocean of Storms) on the western reaches of the Moon. Peppered with a layer of dark pyroclastic glass, the plateau nevertheless presents a strong yellow colour, sometimes described as ‘mustard’.

These colours actually hold great scientific value, offering clues as to the mineral composition of the lunar surface.

Image: Evening in the Ptolemaeus Chain and Rupes Recta Region by Jordi Delpeix Borrell, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Courtesy of the artist.

Find more amazing space stories

13. Only a fraction of stars are actually white

To our eyes, most stars appear white. A few are distinctly yellow or orange, others a pallid blue. But their colours generally appear more subtle than vibrant and often go unnoticed by casual stargazers. Yet photographs of the sky reveal that most show a prominent colour, and only a fraction are actually white.

That’s because stars behave similarly to theoretical objects called black bodies, which absorb all the radiation incident on them. In physics, a black body will radiate as it’s heated up and its apparent colour will depend on its effective temperature. The same is true of a star and, since every star has an effective temperature, it also has peak output colour.

Image: NGC 3521: Mysterious Galaxy © Steven Mohr. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

14. Diamonds are found all over the Galaxy

Diamond, one of the hardest and most lustrous materials on Earth, is formed under extreme pressure and heat deep beneath the surface of the planet. But it turns out that diamonds are not exclusive to our own planet and may be found throughout the Solar System, Galaxy and beyond.

Scientists have proposed that diamonds may be formed in the atmospheres of both Uranus and Neptune. Astronomers have discovered the presence of hydrocarbons in both atmospheres and, under the right conditions, they become the building blocks of diamonds.

In recent years, astronomers have identified a number of potentially diamond-rich exoplanet candidates – worlds orbiting stars other than the Sun. One diamond-rich candidate is BPM 37093, located about 53 light-years from Earth. It is a white dwarf star, once somewhat similar to the Sun, and has since matured into a much smaller, carbon- and oxygen-rich star. Its brightness varies with a pulsating pattern and astronomers were able to use this characteristic to measure how much of the star’s interior has crystalised as the star has cooled. The calculations indicate that as much as 90 per cent of the star’s mass is now a crystal structure – a solid core made of diamond, measuring about 2,000 miles across.

Nicknamed Lucy (after the Beatles song ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’) this star may well be hiding the most valuable diamond yet known, comparable in size to the Moon and 100,000 times heavier than the Earth!

Image: Wanderer in Patagonia by Yuri Zvezdny, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Courtesy of the artist.

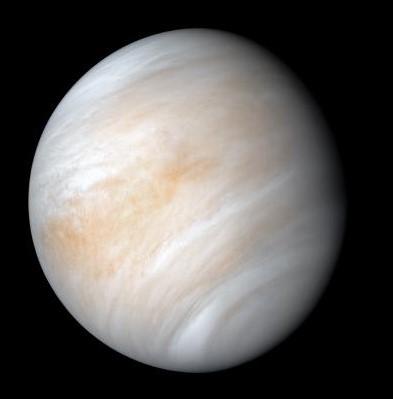

15. It appears that a day on Venus is longer than its year

Venus is sometimes referred to as Earth’s ‘evil twin’ due to the pair’s similar sizes and compositions but very different climates. While Earth has a rotation period of 23 hours, 56 minutes and 4.1 seconds, Venus takes much longer to make a full rotation on its axis, with a period of about 243.025 Earth days. By comparison, it takes Venus just 224.7 Earth days to orbit the Sun – so it would seem that a Venusian day is longer than its year.

Image of Venus by NASA/JPL-Caltech

About the book

This article is an edited extract from Diamonds Everywhere.

Feed your cosmic curiosity with this comprehensive guide to the Universe, featuring 101 out-of-this-world astronomical facts, discoveries and innovations. From gravitational curls to strange new worlds; the night sky to the end of time – you’re sure to find something you never knew before in this mind-expanding book, and with stunning images from the world's greatest observatories, every turn of the page offers a visual treat.

Buy your copy of Diamonds Everywhere now from the Royal Museums Greenwich online shop.

About the author: Tom Kerss

Tom Kerss F.R.A.S. is an astronomer and the author of numerous bestselling books about the night sky for both adults and children. Having worked at Royal Observatory Greenwich for more than six years, he now shares his passion for the stars with people all over the world, delivering courses, podcasts and media interviews. Tom loves nothing more than to seek out the darkest and most beautiful skies on Earth, but he does most of his stargazing from his home in London.

Follow Tom on Twitter or Instagram, or visit his website.

Header image: The Rho Ophiuchi Clouds © Artem Mironov. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. overall winner of Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2017