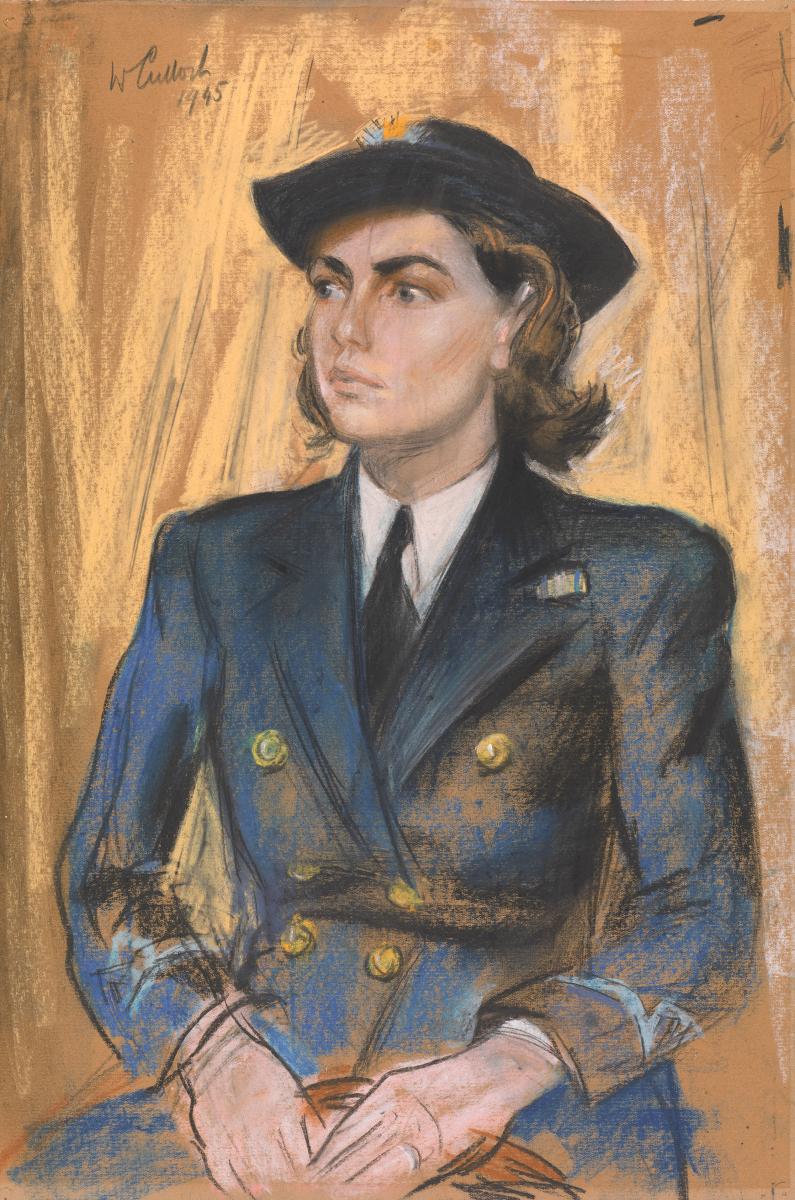

In 2022 Royal Museums Greenwich acquired a pastel portrait of an officer in the Women’s Royal Naval Service (Wrens). The portrait is a striking work of art, full of character and personality.

There’s just one problem: we do not know the name of the woman depicted. To coincide with the portrait going on display in the Queen’s House, we’re on a mission to determine the identity of this unidentified sitter.

From archival records and provenance research to public appeals and possible names, Dr Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art (Post-1800) gives an insight into the work involved to find the unknown Wren.

The hunt is still on to identify the mystery woman in the portrait. Read on to learn more about the research so far, and contact RMGenquiries@rmg.co.uk if you have any suggestions.

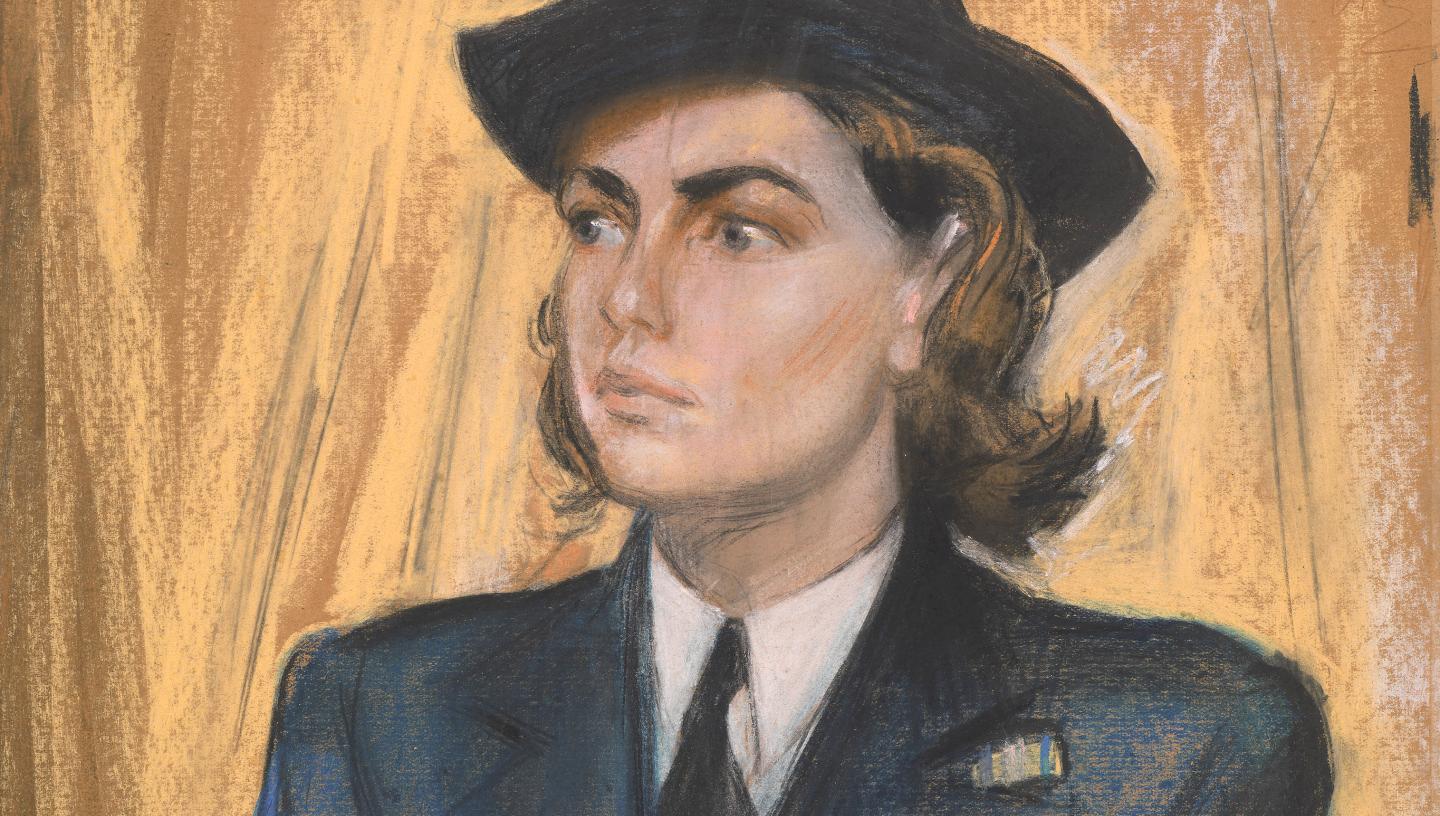

Who could she be? Looking for clues in the portrait

The details in the portrait provide important clues to the woman’s identity. Featuring a single pale blue ring around each cuff, her uniform shows that she held the rank of Third Officer, the most junior officer rank in the Wrens.

The Women’s Royal Naval Service, also known as the Wrens, was first established in 1917. Although dissolved in 1919, it reformed at the outbreak of the Second World War and ultimately merged with the Royal Navy in 1993.

The woman also may have been awarded a medal for her service, since what appears to be a blue-and-white medal ribbon is shown peeking out from under her lapel. She also seems to be wearing a wedding or engagement ring.

The portrait is inscribed with the signature of the artist, Joseph McCulloch, and the date, 1945.

Are there links to the artist?

Our initial research focussed on the portrait’s artist, Joseph McCulloch. Could records of his career reveal the name of the mystery officer?

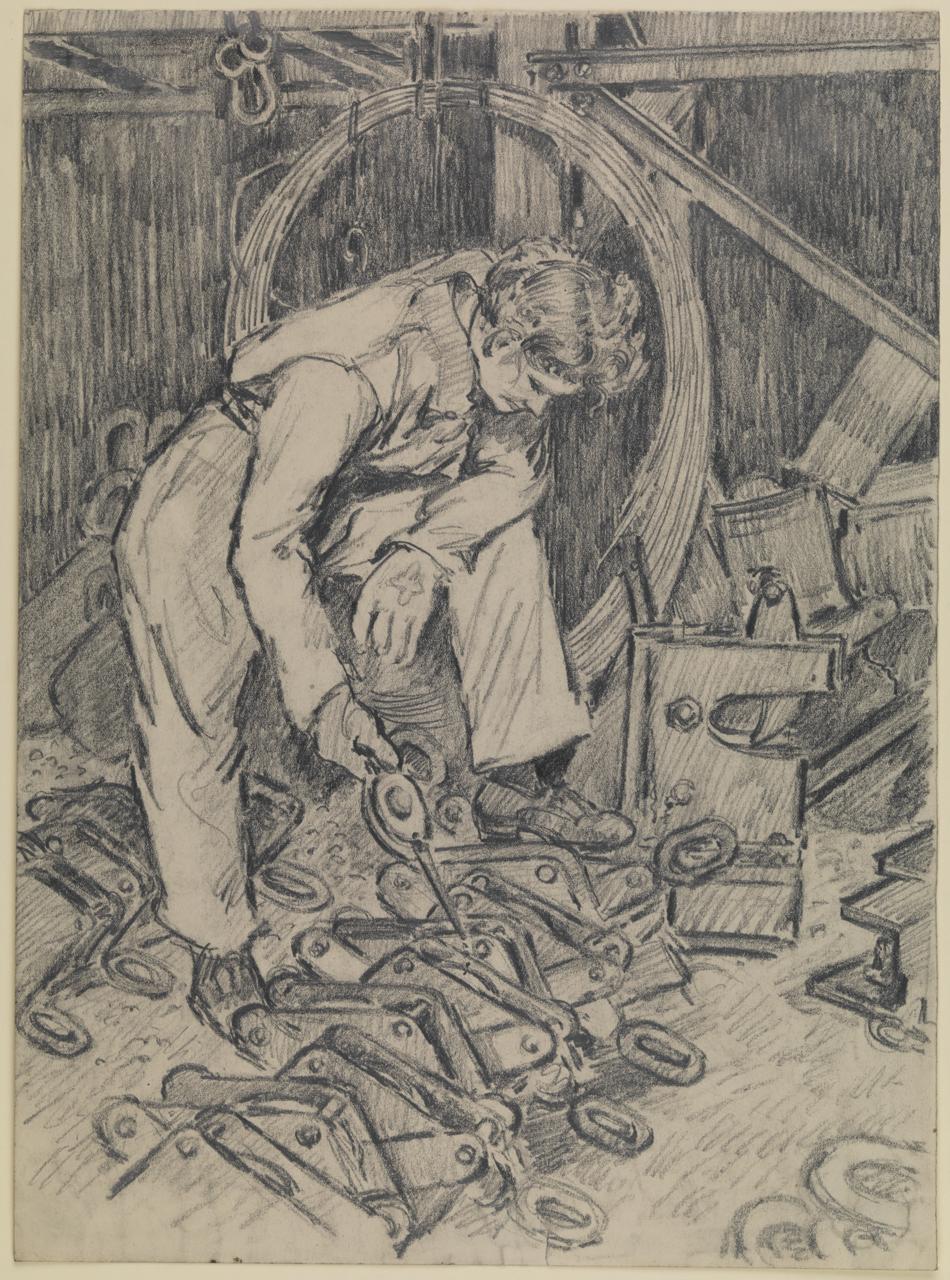

The son of a steelworker, McCulloch was born in Leeds in 1893. He moved to London when he received a scholarship to study at the Royal College of Art. He taught drawing at Clapham School of Art, then at Goldsmiths, and made his home in Chelsea, where he was a prominent member of Chelsea Arts Club.

Nicknamed “Mac”, he was known locally for his colourful language and acerbic sense of humour, as well as for the gold earrings and red neckerchief that he habitually wore. He struggled with health problems and financial difficulties in later life and died at Rothwell in Yorkshire in 1961.

McCulloch was not a high-profile artist, so finding information about his work proved difficult. As a first step, we tracked down his surviving family. While they were delighted that his work is now in the collection of a national museum, they did not possess any archives or information relating to the Wren officer’s portrait.

Next, we trawled through old exhibition catalogues from galleries and institutions where McCulloch is known to have shown his work, including the Royal Academy, the New English Art Club and the Redfern Galleries. This search turned up many landscapes by McCulloch but few portraits of any kind and none of women in the Wrens.

Finally, we tried the archives of the War Artists Advisory Committee (WAAC). During the Second World War, the WAAC was responsible for acquiring and commissioning artworks for the nation. In 1944, the Committee paid McCulloch for a portrait of volunteer firefighter Tony Smith, who had had been awarded the George Cross – the highest civilian award for bravery – after rescuing survivors from a bombed building in Chelsea. This shows that, from his studio in Chelsea, McCulloch was creating portraits of local people involved in the war effort. However, his correspondence with the WAAC did not mention any portraits of Wren officers.

Who owned the portrait?

Art historians often use provenance research to find out more about artworks. The provenance of an artwork is its ownership history: who it belonged to at different times and how they acquired it.

Unfortunately, our efforts to trace the provenance of the Wren officer’s portrait were unsuccessful. The Museum purchased the portrait from an art dealer, who had himself acquired it at an auction, but after that the trail went cold.

Do you recognise her?

Having drawn a blank in our research, we decided to ask the public for help. Perhaps someone might recognise the person in the portrait from a family photograph? Or maybe an internet sleuth would find a crucial piece of evidence that we had missed?

The response has been overwhelming. We have been inundated with messages of support and ideas for further research. Many people have suggested possible identities for the Wren officer.

Unfortunately, none of the suggestions so far have been proved correct. Some have been ruled out entirely. The most common issue has been that of rank: from her uniform, we know that the woman in the portrait was a Third Officer, so we have had to exclude suggested women who held a different rank, such as Second Officer or Leading Wren. Other suggestions may be right, but we do not have enough evidence to say for certain.

We are still hopeful that we will discover the Wren officer’s identity, but this research has always been about more than just one portrait. The Women’s Royal Naval Service was a large organisation, through which a wide range of women contributed in many different ways to naval operations. Every Wren has her own story to tell.

Discover more great art

Sign up to the art newsletter for more information about Royal Museums Greenwich's art collection, and learn about upcoming exhibitions and events.

Your ideas and suggestions

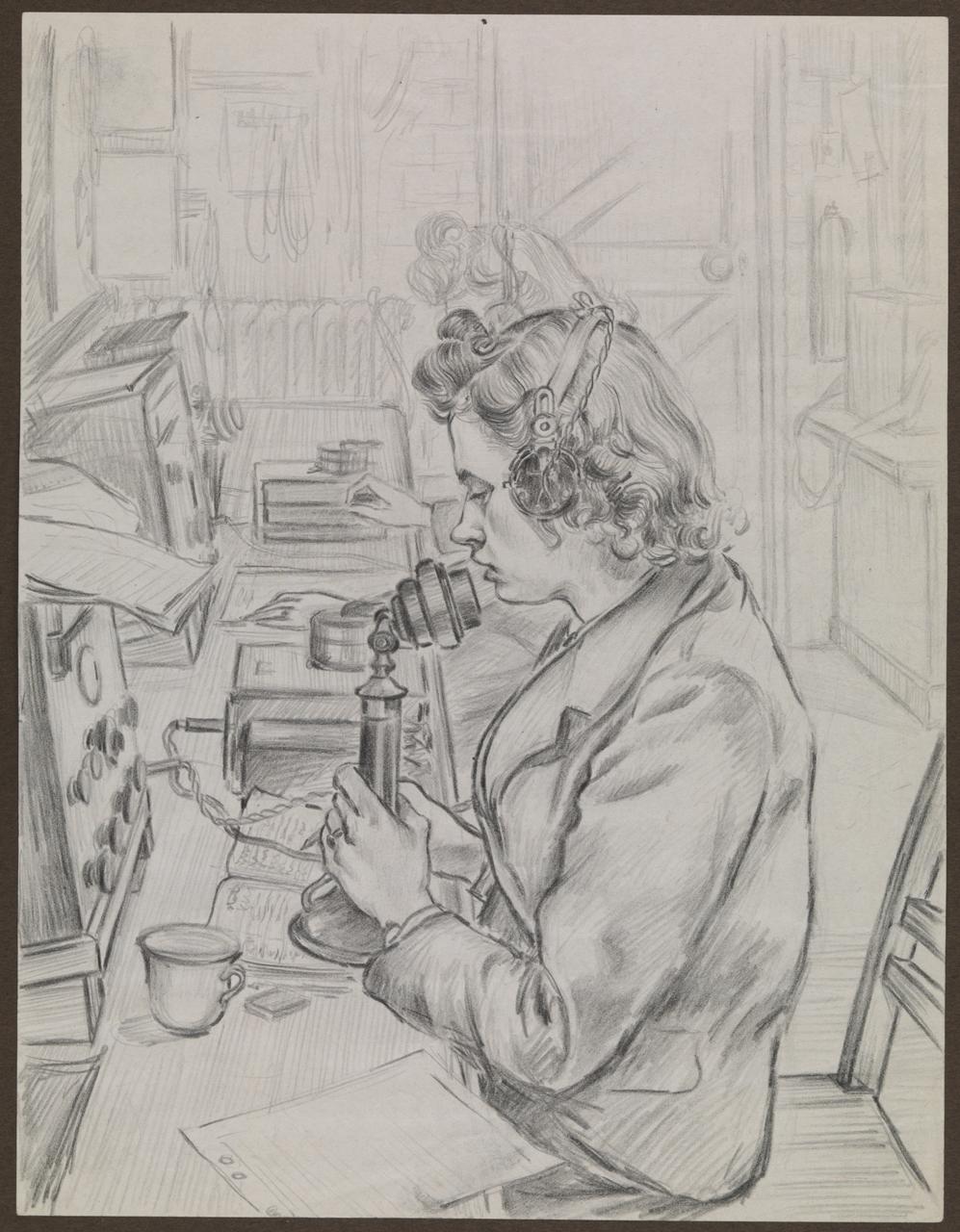

Even if it has not yet identified the woman in the portrait, our public campaign has provided fascinating insights into the variety of individuals who joined the Wrens and the range of work that they did.

Discover some of the most fascinating suggestions we have received below.

Nancy Spain (1917–1964): detective novelist and comedian

Nancy Spain joined the Wrens in 1940. She worked as a driver in Tyneside, before becoming an officer and moving to the Wrens headquarters in London, where she worked in the Press Office.

She later had a successful career as a comedian, broadcaster and author of detective novels before her tragic death in a plane crash. In the 1950s, Spain was a regular at Gateways, a lesbian club in Chelsea, where she also lived with her partner, Joan Werner Laurie. Could she have known Joseph McCulloch in Chelsea?

She had a distinctive look with dark hair and heavy eyebrows, features shared by the woman in our portrait.

However, Spain held the rank of Second Officer in 1945 and left the Wrens in February that year. She therefore cannot have been the Third Officer depicted in McCulloch’s portrait.

Maria/Mary Elizabeth Ferguson (1923–2006): naval heroine

Maria Elizabeth Ferguson (known as Mary in the UK) was born to British parents in Argentina. Nicknamed ‘Johnnie’, she booked a ticket as a passenger on a cargo ship, the Avila Star, sailing from Buenos Aires to Liverpool in March 1942, intending to join the Wrens once she reached the UK. However, the Avila Star was torpedoed in the North Atlantic.

Ferguson suffered a head injury but managed to swim through oily water to a lifeboat, where she helped to care for others. The lifeboat was adrift for twenty days before it was picked up by a Portuguese naval vessel. Half of the lifeboat’s passengers died from thirst, starvation, injuries and exposure. Ferguson sustained 48 seawater boils but later made a full recovery. She was flown from Lisbon to Bristol, where she joined the Wrens and served as boats’ crew at Devonport until the end of the war.

For her bravery and selflessness during the lifeboat ordeal, she was awarded the British Empire Medal and became one of only four women to ever receive the Lloyds War Medal for Bravery at Sea. This medal had a blue-and-white ribbon similar to the one depicted in the pastel portrait. Could Ferguson be the mystery woman?

Unfortunately, Ferguson’s highest recorded rank was Leading Wren. She was never a Third Officer.

Constance Leonora Pearn (née Hale) (1918–2001): typist for anti-submarine warfare unit

Constance Leonora Hale was born and grew up in Huddersfield. She served in the Wrens during the Second World War and married Donald Pearn in her hometown in October 1944.

In 1943, she was a shorthand typist in the motor yacht HMS Philante. The Philante led training exercises for the Western Approaches Tactical Unit, which devised strategies for anti-submarine warfare.

Because of her service aboard HMS Philante, Pearn was one of only two Wrens to receive the Atlantic Star. This medal was awarded to British service personnel who had spent at least six months at sea during the Battle of the Atlantic. The ribbon for the Atlantic Star is green, white and blue. Could this be the medal depicted in the pastel portrait?

Pearn, however, cannot be the unknown woman because she was a Petty Officer, not a Third Officer. To confuse matters, there was a Third Officer in the Wrens called Constance Mary Hale, but she was a different person.

Elsa Megson (1911–2004): aerial photographer

A keen amateur photographer, Elsa Megson resigned her position as secretary of Buxton Camera Club to join the Wrens in 1941.

She continued to develop her interest in photography through her war work, training as an aerial photographer with the Fleet Air Arm. This involved taking photographs of the ground through a hole in the floor of an aircraft.

After the war, she became a professional photographer in Godalming, specialising in horticultural and garden photography.

While Elsa’s career is fascinating, she does not appear on any lists of Wren officers. It seems she never attained the rank of Third Officer.

Patricia Mountbatten (1924–2017): 2nd Countess Mountbatten of Burma

Patricia Mountbatten was the eldest daughter of Admiral of the Fleet Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma. She was the cousin of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and a descendant of Queen Victoria.

In 1943, she joined the Wrens as a signals rating. Two years later, she became a Third Officer and was sent to join South East Asia Command (SEAC) in Sri Lanka, where she met her future husband, John Knatchbull, 7th Lord Brabourne. They returned to London and married in October 1946. She became Countess Mountbatten of Burma when her father was assassinated in 1979.

Mountbatten had a similar heavy-eyebrowed look to the Wren in the portrait and she was a Third Officer in 1945. However, she was in Sri Lanka at that time and therefore could not have posed for a portrait in her new uniform in London. It also seems unlikely that an aristocratic young woman like Mountbatten would have sat to a little known, bohemian artist like McCulloch.

Elsie Stanbridge (née Hewson) (1916–?): ambulance driver and mail clerk

Elsie Hewson volunteered as an ambulance driver for the Civil Defence Service in her hometown of Hartlepool, before joining the Wrens in 1940.

She worked as a mail clerk in London, ensuring that postal deliveries continued throughout the war. During this time, she lived on Cheyne Walk in Chelsea and enjoyed looking at the shops in Knightsbridge on her way to work.

In 1943, she met Roland Stanbridge, who was in the Royal Marines, and the couple married the following year.

Stanbridge’s granddaughter contacted us because she thought that the portrait looked like her grandmother, who could conceivably have met Joseph McCulloch in wartime Chelsea. However, Stanbridge’s highest rank was Leading Wren.

Why this portrait matters

The portrait represents an important addition to Royal Museums Greenwich’s collection.

While Wrens are represented in the Museum collection through uniforms, medals and photographs, the recently acquired pastel is our first formal portrait of a Wren.

It is also our only portrait of a woman in naval uniform – a fact that reflects the chronic underrepresentation of women in war art.

Increasing the number of women’s portraits in our collection will take time, but the acquisition of this portrait is a meaningful step towards that goal.